|

|

|

Taxonomy and description

|

Transit Oriented Development |

Transit Adjacent Development |

|

|

Table 1: Transit Oriented Versus Adjacent Development (VTPI, 2013, citing Renne 2009)

This instrument is closely related to the use of land use planning to reduce the need for personal motorised travel and public transport services.

How can land use planning encourage the use of public transport?

Several studies indicate that if development is planned specifically to encourage public transport there can be a significant reduction in per capita car travel. Public transport nodes, including rail stations, serve as a catalyst for more accessible land use by creating higher density, mixed-use, pedestrian- and cyclist-orientated centres. Households living in such neighbourhoods tend to own fewer cars, and people working in such areas are more likely to commute by alternative modes (partly because they do not need a car for lunchtime errands) (Cambridge Systematics, 1994).

These factors result in higher levels of public transport commuting, increased non-motorised travel for non-commuting trips (such as shopping and trips to school), and reduced car travel. As a result of these various factors, there tends to be a "leverage" to much greater reductions in vehicle travel than that which is directly shifted from car to public transport. International research summarised by Newman and Kenworthy (1998, p. 87) indicates that each passenger-kilometre of rail travel appears to be associated with a reduction of 5 to 7 kilometres of car travel through these various mechanisms.

Badoe and Miller (2000), in summarising the work of previous researchers, concluded that public transport service can facilitate land use development patterns, but is only one of many factors, and will not cause significant land use or travel behaviour change by itself. If an area is ready for development, improved transit service (such as a rail station) can provide a catalyst for higher density development and increased property values, but it will not by itself stop urban decline or change the character of a neighbourhood (VTPI, 2002).

In practical terms, this means that there are two specific but inter-related ways in which land use planning can encourage the use of public transport:

The general principle is thus to ensure that trip origins and destinations are arranged in nodal or linear patterns which are compatible with the demand patterns needed to ensure that public transport services, both bus and rail, are viable and efficient.

It is important to note that the effects of land use planning on public transport use are likely to be greatest where sufficiently strong regulation of land use is in place.

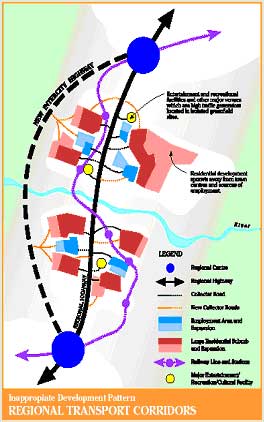

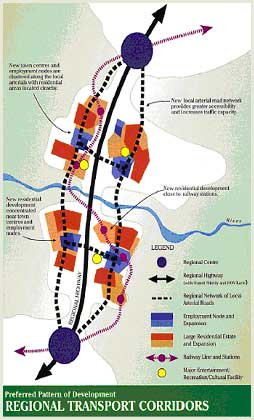

In its guide 'Shaping Up', the state government of Queensland (Government of Queensland, undated) offers guidance on the design of public-transport-friendly development, in the form of idealised 'how to do it' and 'how not to do it' examples, one set of which is shown below, for transport corridors in urban regions.

The Guide describes the principles involved in the design of transport corridors for improved public transport as follows:

"Urban growth often takes place along corridors created by major highways or railway lines. The way in which these transport corridors are planned and designed at the regional level can have major implications for public transport use. Corridor planning and the distribution of land uses also impacts significantly on public transport costs, operational efficiency and funding requirements".

The Guide suggests the following approaches to good practice:

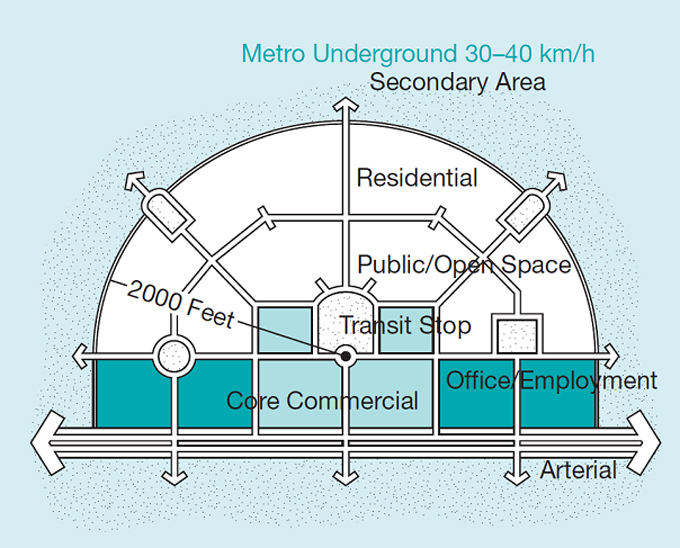

The UN Habitat report includes a diagram illustrating similar concepts, based on earlier work by Calthorpe (1993).

Neighbourhood-scale TOD site design, with mixed-use development within a walkshed (650 metres) of a public transport stop, with densities tapering with distance from the station (UN HABITAT, 2013, citing Calthorpe, 1993).

It should be noted that large scale park and ride facilities can conflict with accessibility and liveability benefits: a railway station that is surrounded by large parking areas and by main roads with heavy traffic is unlikely to provide the best environment for residential development or for pedestrian access. As part of land use planning, it is thus important that such facilities be properly located, designed and managed to minimise such conflicts.

Other than the rail and bus infrastructure and vehicles, this policy

instrument is not dependent upon technology.