| What do we mean by optimisation?

Strictly optimisation means finding the best solution to

a given set of transport problems, or the best strategy to

meet a given set of objectives. In practice, cities will not

often be free to implement the combination of policy instruments

which is theoretically best for them, either because they

do not have overall control on all policy instruments (for

the reasons given in (Section

3) or because they face barriers of finance or acceptability

(Section 10). In practice,

therefore, optimisation involves identifying the best solution

within a given set of constraints.

Why should we use optimisation methods?

Traditionally, cities and their consultants have attempted

to determine the best strategy through a process of identifying

a possible solution, testing it (Section

12 ), appraising it (Section

13) and then seeking improvements. These improvements

could either be straightforwardly to increase performance,

or to overcome barriers such as lack of finance or limited

public support. However, this process can be inefficient;

time will be wasted on testing inappropriate strategies, and

there is no guarantee that the best strategy will be found.

Thus the benefits of optimisation are both in developing more

effective strategies and in doing so more rapidly. In an early

example in Edinburgh, an initial study used some 70 model

runs to develop a “best” strategy; a subsequent

study using optimisation methods found a combination of policy

instruments, after 25 model runs, which increased economic

efficiency by a further 20%.

Optimisation is thus a very elegant way of choosing the best

strategy. Even if we do not often want to automate the decision

making process in this way, experience shows that it produces

interesting new strategies that would not otherwise have been

thought of.

How does optimisation work?

Formal optimisation is a relatively new concept in the analysis

of integrated land use and transport strategies. We describe

it further in the PROSPECTS Methodological Guidebook, and

in a more recent report on the generation of optimal strategies

for UK cities. It involves maximising a quantified objective

function within a given scenario, and subject to a given set

of targets and constraints, by using a given range of land

use and transport policy instruments.

How are objectives represented?

At the heart of this policy optimisation process lies the

definition of the objective function, which is a quantified

measure of the policy-makers’ objectives and the priorities

between them. The objective function should be consistent

with the appraisal framework (Section

13), and can thus be based on either a Cost Benefit Appraisal

or a quantified Multi-Criteria Appraisal, in which weights

are assigned to the individual objectives. The value of the

objective function for each set of instruments and their associated

levels is derived by running a land-use transport interaction

model (Section 12).

How are scenarios and constraints reflected?

Scenarios can be selected based on the principles in Section

11. Often the strategy is optimised against one scenario,

and the optimal strategy is then tested for robustness against

other scenarios. In due course methods may permit optimisation

to be pursued for all scenarios, with techniques of appraisal

under uncertainty being used to minimise the risk of poor

performance under more demanding scenarios.

Constraints can be dealt with in two ways. Political barriers

can act as a constraint on which instruments may be considered

and within which ranges; for example parking charge increases

of above a given level may be considered unacceptable. Financial

barriers and outcome targets can be incorporated within the

optimisation process; for example a restriction on capital

investment could be used to rule out those strategy options

which exceeded it. In either case the optimisation can be

repeated without the barrier to demonstrate the benefit of

removing it. This can help in making the case for changes

in legislation (Section 10).

How are policy instruments selected?

Policy instruments can be chosen from the list in Section

9. In due course, new approaches to option generation

may help to suggest which policy instruments should be considered.

A formal optimisation process is most useful in considering

a package of strategic instruments which are expected to have

a significant impact on the city. They will reflect the key

strategy elements in Section

11. Most strategic instruments have some level which may

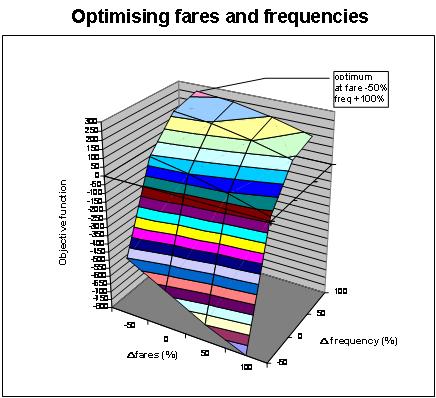

be varied (e.g. a price) which can be optimised. The diagram

shows an optimum for a range of levels of fares and frequencies.

Some, such as discrete road and rail projects, are either

included or not. Once an optimal set of strategic instruments

has been selected, other second order elements of the strategy

(Section 11) may be added

in ways which enhance the overall policy.

When are optimisation methods appropriate?

When a city is assessing a relatively small number of policy

instruments, or simply assessing one new proposal within a

given strategy, formal optimisation is unlikely to be needed.

However, where the number of options is substantial it will

often be much quicker and less expensive to use a model in

conjunction with an optimisation method than to use the model

alone. Where there are several scenarios to consider, or constraints

whose impact needs to be assessed, optimisation can prove

even more valuable.

|